Interview with Elene Naveriani

Wet Sand comes four years after your first feature film, I Am Truly a Drop of Sun on Earth. In the meantime, you have made a short film and a documentary. What is behind this second feature film?

My older brother, Sandro, who is a screenwriter, started working on the script. The idea came totally from him. He asked me to join him, and we started to develop the project to think about how to stage it. At a certain point, Sandro preferred that I direct the project alone, the questions to do with staging had obviously made him tend towards my cinema. It turned out to be a gift. In my cinematographic practice I try to make the invisible visible, to make unheard and subsidiary voices heard and to create a central space for marginalised lives. My cinematographic practice is above all a language of resistance in the face of denial and forgetfulness. Even though there are still a lot of things in this film which are due to my brother's own input, if only in terms of its structure. Sandro is a professional screenwriter, and "Wet Sand" is without a doubt the most structured of my films, the neatest from the point of view of the narrative, perhaps the most classical - although this notion is very relative.

Did you try to break this classicism, to parasitize it?

No, not necessarily. I rather enjoyed seeing the structures working. It went perfectly subject, and I took great pleasure in observing how things unfolded. I was then able to deconstruct things, but more in the actual detail of the scenes. It was in the directing that I was able to be the freest. It's quite interesting to start with a very written script and to feel so much the freer when it comes to directing it. If there were a conflict between the classical path and a more modern researched approach, it is in directing that this would be expressed with abundance.

The casting?

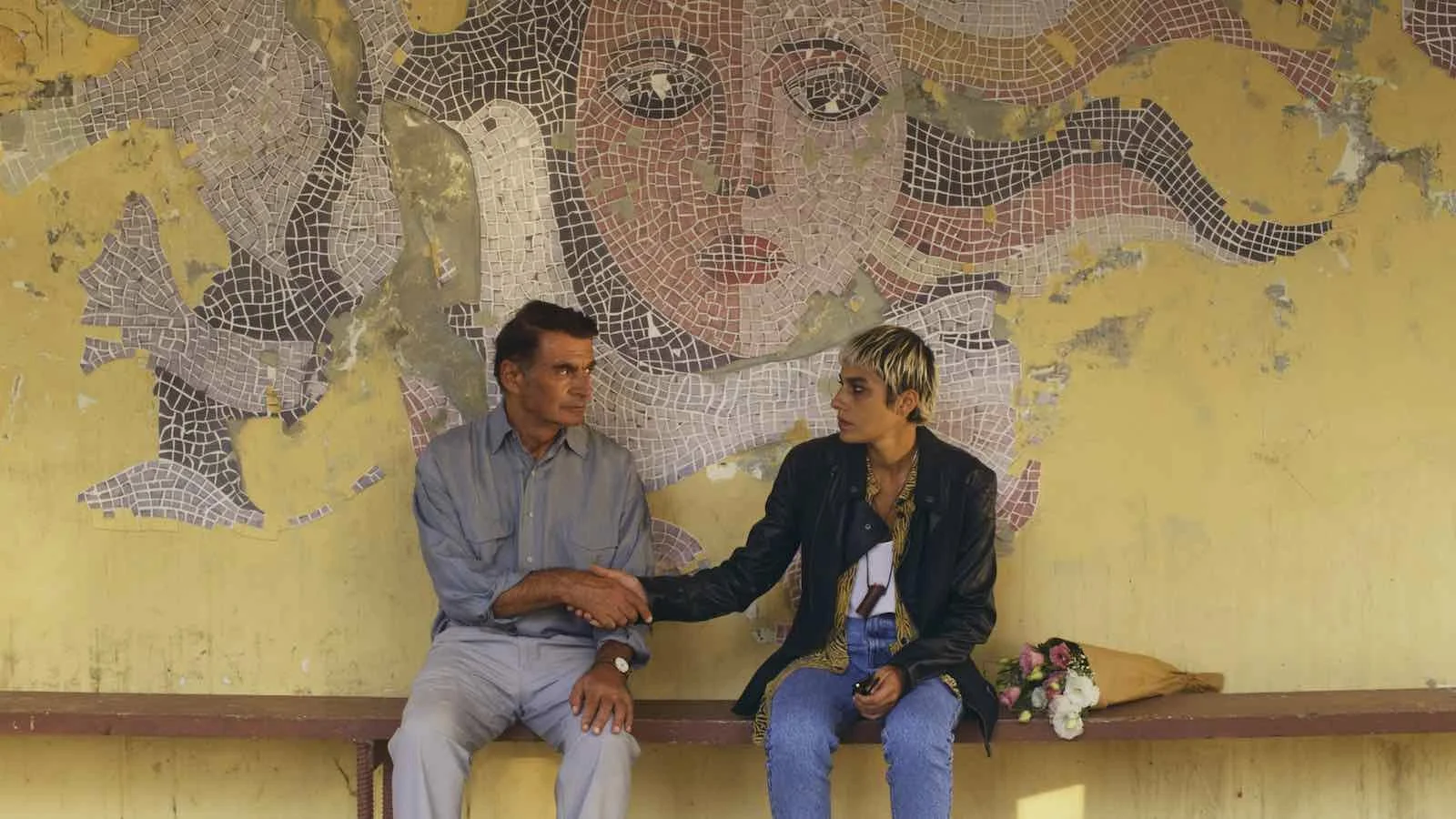

It was done in Georgia. That's the difficulty, because the subject was problematic. For the main roles, many professional actors refused to take part in the film because of the subject. The casting complication was also a sign for me that it was important to make this film in this place and at this exact time. For Amnon, the main character, I didn't know where to find him, but I ended up meeting a person who was a lecturer at the university and who taught Latin. I liked him, his sensitivity, his gestures, his movements, it was exactly what I had dreamt of finding. He agreed to take part, in spite of the fear he had. He had been through a somewhat similar experience. Moe, she is not a professional either. This is her first film role. The others come from the theatre, from the street, from the village. In fact, all the actors (I don't like to say non-actors - as soon as you are in front of the camera, you become an actor with more or less experience) who agreed to be part of the film, wanted to express their position on the current political and social situation in Georgia. They knew that being in the film could cause them problems in their personal or professional lives. I am proud of them, they are brave people.

Where was the film made?

On the Black Sea, not far from Poti. In a tiny fishing village. The kind of place where other than life among the few inhabitants. It's quite symbolic of what happens in Georgia: a highly centralised power and a periphery that is, so to speak, abandoned. Sandro had wanted to set the action there, because of this very isolation. When I first saw the village, I immediately agreed that it was the ideal place for our story. It was important to set the story in a very vast and remote place to emphasise the people, their feelings, their fears and their struggles. Apart from the conceptual aspects, it is a very cinematographic village and it has a rather universal character: it could be in the south of Italy, in Spain, in Croatia or in Japan. A dry and hostile village, closed. Stuck in its traditions, in which one can feel as if everything is dead, leaden. The feeling it spreads is universal. Also, the contrast between movement and stagnation. A nature (a sea in movement) that never stops, that moves, that speaks, that changes and the people trapped in their traditions and fears. And also in the film, there is this aspect of generational conflict, something that moves and something that stops and dies. Nothing ever moves, despite the waves and the huge sun.

The film was mostly produced in Switzerland?

Yes, this subject would not have received official funding in Georgia without the initia lSwiss involvement. The subject is too much of a problem and it would have been censored. Switzerland, where I live partly and where I studied film (at the HEAD in Geneva) offers me this opportunity to tell the story of Georgia freely. It is a privilege that people in Switzerland give me the possibility of this space where I can tell the story of Georgia. And since I live and work most of the time in Switzerland, it was natural that the film be mainly financed in Switzerland. We also had a Georgian production company on board. It is an official co-production between maximage (Switzerland) and Takes Film (Georgia). Like me, I have a part of both countries in me. I started making films here in Switzerland. So, Switzerland is an important element in my cinematographic practice. I have contacts, colleagues here who are precious to me. But at this moment, there is not a day that I am not inhabited by Georgia. What moves me, touches me and angers me as a filmmaker, is always in Georgia. I have a critical but passionate relationship with the country. I would like it to be different, better, but I don't want to shun it in any way. It is a criticism from within, of politics, society and religion. This criticism is not easy for me. It also hurts me a lot. Georgia is still my country. Making my films in Georgia is my way of doing something for this country, not against it.

The chief operator is also Georgian?

Agnesh Pakozdi is Hungarian! I met her in Berlin. All my films were made with her, from the beginning. We have an instinctive relationship. It's easy for me to work with her, we are on the same wavelength, she translates what I imagine and what I think into the image. It's very special for me to be able to rely on her. We are an only brain on the set.

Do you think it brings an outside view of Georgia?

A distance perhaps, but not a tourist's point of view. This question touches on something important to me: I have been away from Georgia physically for several years. This creates a certain distance in my way of seeing things, sometimes I even feel alien to everything that happens there. Sometimes I feel extremely close to it. I think that in my work I bring distance, not an outsider's view. Certainly not an exotic and miserable view of the country. So, I need for Agnès, in her image, to have a familiarity with the country. We have already made many films together in Georgia, and she certainly does not bring a postcard point of view.

Your film shows people who suffer, if not die, from loving in secret, or hiding from loving, lying to religious and social authorities that are heavy, old, almost impossible to move.

That's exactly what it is. That's exactly what it is. One of the layers of the film expresses the need to shake up traditions, to revalue them. The patriarchal heteronormative culture that prevents society from evolving, promotes pseudo-identity and annihilates diversity. This is what is happening in many countries these days. But what is in the film reflects only a small part of . The reality is stronger and crueller than the film, every day something happens that shows that Georgia is a country where you are not allowed to love and exist together, if you like them. That is why I suggest something drastic at the end of the film. We also have a place to exist and we will exist, but it will be a long way.

What rights are granted in Georgia to LGBT+ people?

None. There is a constant repression against the queer community. The church has a role to play in this situation, but also the global geopolitical situation: politically, Georgia is aligned with Russian decisions. whatever the subject. And LGBT issues are dealt under Russian influence. It adopts the line taken by Moscow. The country is too small compared to the colonialism that Russia exerts on it, its influence, its economic weight on Georgia. The daily life of queer people is very, very hard today, but the associations, the alternative actions are trying to , but outside any legislative apparatus that could guarantee them security. There is a jacket in the film, which is right behind you as we speak, and it has this inscription on it: Follow Your Fucking Dreams...Yes, it's very important to me, it's not just a costume or a decorative element. I created it for the film, it was already in the script. I come from a punk heritage, with the slogan as a weapon. The punk slogan was No Future. My slogan is more positive: Follow the fucking dream...There is a lot of talk about a Woman's gaze, of a feminine point of view.

Does your film subscribe to this?

What is a feminine point of view? I don't know, because myself I don't know if I should subscribe to the feminine or the masculine point of view anymore, I have de/identified myself. I am more interested in the disorder of gender than in its essentialist definition.

Do you think that there is a political perspective on the other hand?

Yes, absolutely. That is clear to me. Totally. Making this film is a form of activism. I can talk about something that is happening politically today in Georgia, or elsewhere. But of course, there are different perspectives, but different in what way? Can this difference be summed upas gender alone, as feminine alone? Each director has her own sensitivity. What interests me is that the person behind it has her own story, her own culture, her own political culture, her own construction. To reduce this to an battle between the female and the male view is too quick for me. The differences are deeper and more relative, for me. I can only see myself from Elene's point of view. But still, I think cinema and storytelling are much more interesting nowadays, with less white, heteronormative male points of view.

What are your plans after this film?

I am writing two feature films. One is an adaptation of a Georgian feminist novel published this year, called Tamta Melashvili: Blackbird, Blackbird, Blackberry. And for the past six years I have been working on a project about Saint Nino, the saint who brought Christianity to Georgia in 300 AD. It's a complex project but one that is very important to me. The contrast between the worship of this woman, who is the very body of Georgian identity, and the extreme misogyny of the church today in Georgia. I am writing my own saint, my own Nino

Director

Elene Naveriani

Date of release

2021

Running time

115 min

Rating

12A

Country of origin

Georgia, Switzerland

Language

Georgian (s